Source: https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/factcard_1.jpg

BREAKDOWN

India and UNPKOs

Korean War (November 1950 – July 1954): India deployed the 60th Indian Field Ambulance, a parachute-trained medical unit comprising 17 officers, nine junior commissioned officers (JCO) and 300 jawans in the Korean War. The unit was awarded the President's Trophy on 10 March 1955 by the then president of India Dr Rajendra Prasad. This is the only mission to be awarded the President's Trophy till date.

Indo-China (1954 – 1970): India deployed an infantry battalion and supporting staff during the crisis in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. The mission included monitoring, ceasefire and repatriation of prisoners of war. As many as 970 officers, 140 JCOs, and 6,157 jawans were deployed.

Source: https://www.thequint.com/videos/news-videos/un-peacekeeping-missions-india-the-largest-contributor

More than 200,000 Indians have served in 49 of the 71 peacekeeping missions established around the world since 1948. Currently, there are around 6,700 uniformed peacekeepers from India, the vast majority of them in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in South Sudan.

India has also provided 15 Force Commanders to various missions, and was the first country to contribute to the Trust Fund on sexual exploitation and abuse, which was set up in 2016.

India’s longstanding service has not come without cost; as of 30 June 2018, over 160 Indian peacekeepers have paid the ultimate price while serving with the United Nations.

From 2007-2016, there were nine rotations of all-female police units from India, whose primary responsibilities were to provide 24-hour guard duty, public order management and conduct night patrols in and around the capital, Monrovia, while assisting to build the capacity of local security institutions.

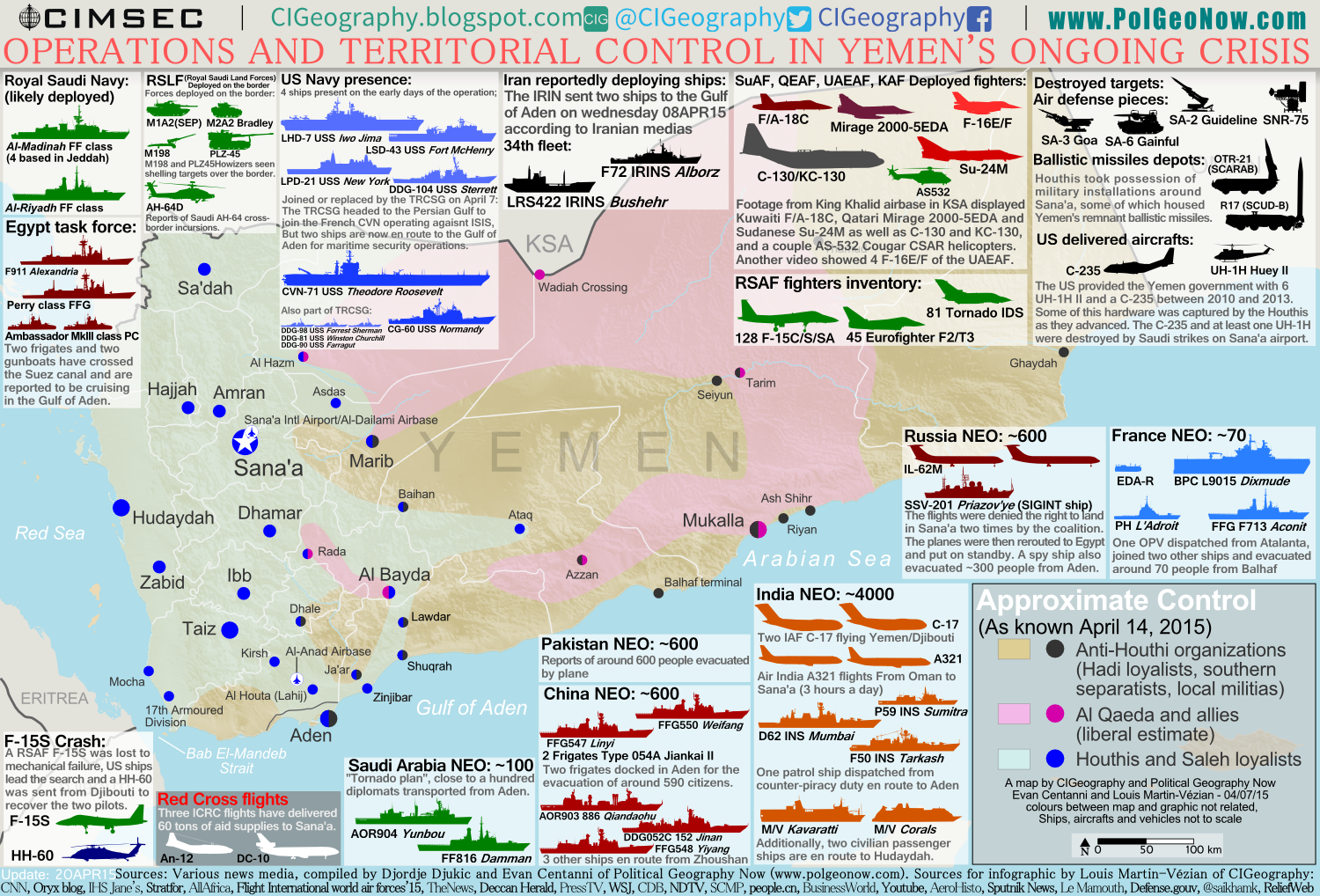

Source: https://www.thehindu.com/multimedia/archive/02370/Yemen_suhasini__3__2370039a.jpg and https://www.thehindu.com/specials/the-great-yemen-escape-operation-rahat-by-numbers/article7089422.ece

Source: http://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/yemen_cig_pgn_cimsec-17apr15.png and https://cimsec.org/the-roles-of-navies-in-the-yemeni-conflict/15901

CHINA IN UNPKOs

Source: He Y. (2019) China

Rising and Its Changing Policy on UN Peacekeeping. In: de Coning C., Peter M.

(eds) United Nations Peace Operations in

a Changing Global Order. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

China also attaches great importance to peacekeeping personnel training. It has invested heavily in setting up peacekeeping training facilities and uses them, among other things, as institutions for relevant international cooperation. China established China Peacekeeping Police Training Center in 2000 and the Ministry of Defense Peacekeeping Center in 2009. Both training centres have advanced facilities, which showcases China’s increased material capabilities as well as strong political will of participating in UN peacekeeping.

Most signifcantly, on 28 September 2015, in

his statement at the General Debate of the 70th Session of the UN General

Assembly and remarks at the UN Peacekeeping Summit, Chinese president Xi

Jinping (2015a, b) announced six important commitments to support the improvement

and strengthening of UN peacekeeping:

First, China will join the new UN

peacekeeping Capability Readiness System and set up a permanent peacekeeping

police squad and build a peacekeeping standby force of 8000 troops. Second,

China will give favorable consideration to UN requests for more Chinese

engineering soldiers and transportation and medical staff to take part in UN

PKOs. Third, in the coming five years, China will train 2000 peacekeepers from other

countries, and carry out 10 demining assistance programs which will include

training and equipment provision. Fourth, in the coming five years, China will

provide free military aid of US$100 million to the African Union to support the

building of the African Standby Force and the African Capacity for Immediate

Response to Crisis. Fifth, China will send the first peacekeeping helicopter

squad to UN PKOs in Africa. Sixth, China will establish a 10-year, US$1 billion

China-UN peace and development fund to support the UN’s work, advance

multilateral cooperation and contribute more to world peace and development.

Part of the fund will be used to support UN PKOs.

When use of force is necessary, Beijing insists that use of force should meet two basic requirements: “one is the authorization of the UNSC, the other for the purpose of self-defense or defense of the mandate” (Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2005).

In recent years, the Chinese academic community is becoming increasingly interested in discussing R2P. In 2012, Ruan Zongze, a senior researcher at the China Institute of International Studies (CIIS), a top Chinese think tank affliated to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), coined the concept of responsible protection (RP) vis-á-

vis R2P (Ruan 2012a). RP has six elements:

1. Any intervention should protect innocent civilians in the country concerned as well as regional peace and stability, rather than specifc political factions or armed forces;

2. The UN Security Council is the only body with the legitimacy to implement “humanitarian intervention”;

3. The necessary precondition for the implementation of force must be that all diplomatic and political means of settlement have been exhausted;

4. The goal of protection should be to prevent or alleviate a humanitarian disaster, rather than the overthrow of a government;

5. National reconstruction after intervention and protection should be given sustained support;

6. The UN should establish a monitoring mechanism, and an effective evaluation and accountability system (Ruan 2012b).

A look at the instances when China has vetoed resolutions in the UNSC shows that it has consistently objected to humanitarian intervention in Syria and voted against such measures 6 times and has similarly objected to measures against Venezuela in February 2019. Details can be found here: https://research.un.org/en/docs/sc/quick